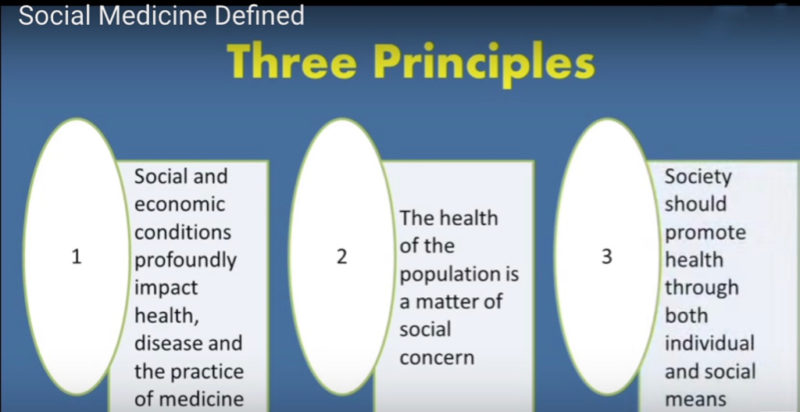

This dialogue continues The Foundry’s ongoing exploration of innovative systemic practices that are building ‘another world.’ We have invited three internationally renowned doctors who are practitioners of Social Medicine, a (relatively) new and proliferating approach to healthcare. Social Medicine is a specialized field of medical knowledge and practice that concentrates on the social, cultural and economic impact on medical phenomena – it is a study of man as a social being in the total environment. And it seeks to understand how health, disease and social conditions are interrelated, and create conditions in which this understanding leads to more comprehensive medical treatment and a healthier society overall.

2007 : Ukrainian National Hall, NYC

"Another" Medical Practice

Our physicians have a difficult time with it … the position of ‘I am a doctor so I’m neutral’ is a primary posture.

Lanny Smith

(all bios as of Oct/2007)

Highlights

The social aspects of peoples’ health require you to think that medicine is a human right, not a commodity,

The social aspects of peoples’ health require you to think that medicine is a human right, not a commodity, and unfortunately in the US, and in our medical schools, that is a strange concept.

Cedric Edwards

Lanny Smith

“Historically the first person to put it into practice was noted German pathologist named Rudolph Virchow, who all medical students encounter in their pathology classes. In 1848, there was an epidemic of typhus – which is caused by lice – and they couldn’t contain it and people were dying like crazy. He came back and said ‘the problem is that the people are poor and we have to address the poverty in order to treat this epidemic.” And they looked at him like he was nuts.”

“Social Medicine practice has been laid over the past 150 years, primarily in Latin America. And as we know ELAM in Cuba is now one of the best medical schools in the world, and teaching from the Social Medicine approach. And not many people know this but Salvadore Allende, before he was elected president of Chile, he was the Minister of Health, he was a public physician. Allende incorporated these approaches into medical practice in Chile, and put it into place in Chile’s healthcare system. You can read his writings in the Journal of Social Medicine. But as we know, he was murdered in the coup. And Pinochet, armed with the economists from the University of Chicago, killed his social healthcare system and replaced it with the American for-profit system. (There’s a great chapter in Naomi Klein’s new book, The Shock Doctrine about the UofChicago economists in Chile after the coup. When those Chicago Boys came in and took over, there was actually no popular support or even interest in the capitalist model, it was enforced, which is quite different from what we were led to believe.)”

Joia Mukherjee

There are 3 things to consider in the practice of social medicine

- what is the social context of the individual?

- What is their societal context; is there something within their community that makes it difficult for a person to have good heath?

eg. if you take the DC blue line subway 6 stops, you lose 15 years of life expectancy. How can you be a doctor and not medically take this into account? It’s a social factor, a community level social factor. - What’s the global social context that impacts on medicine. For example, Haiti has a health budget of $1.75/person/year. What do you think it costs for a infant’s vaccination series? $2.40. So if your health budget is 1.75, what do you do? You don’t vaccinate. And in fact Haiti had the first outbreak of polio in two decades in 2001.

Joia Mukherjee

I’m primarily an AIDS doctor. And when I first started working on AIDS about 13 years ago, I was in Uganda in 94-95. And at the time the community I worked in was 35% HIV positive. Which means that people of childbearing age – from abut 15-40 — were 60% positive for HIV.

It was before there was an HIV treatment available, so we were in primary schools teaching the kids how to protect themselves against AIDS, how it’s transmitted, how you an prevent it etc. We did this program for two years in 92 schools. The kids who’d been selected for our classes were ‘leaders’ in their class; they were going to be peer educators and go back to these 92 schools and teach about AIDS over the entire year. They were given space in their curriculum to do this, the teachers were involved etc.

After our 3 week course in each school, we said to the students okay, now give us your 5 main risk factors for HIV and then we’ll design a program with you to focus on those specific risk factors. And for all the kids their #1 risk factor was the same; they said it was poverty. So for me this was a huge lesson, because their social context of the disease, of their lives, was what put them at risk for this disease that we consider sexually transmitted, infectious, epidemic… . So why did poverty put them at risk? Why do you think the kids told me — these are kids from 11-14 – imagine having the insight at 11, that poverty puts you at risk for AIDS, that was shocking to me. So what do you think, what were they thinking when they said poverty? Food. They’re hungry. And to eat … what people – especially girls and women – have to do to get food…

And in these kids’ case, one of the specifics they talked to us about was school, which in most poor countries is not free – primary school is not free in Uganda. And children, particularly girls, if they don’t know how to read and write, they know they’re going to end up being domestic servants, that’s a fact. If they know how to read and write, maybe they have a chance at getting out poverty. So these kids were making a decision … maybe there’s some man who will pay for their school … maybe he’ll feed them … in exchange for sex, so they’re making the decision that that risk is less than the risk of being a servant. And one might say they’re actually making the right choice.

So it’s not a case of our educating them, it was their educating me about the social context, in this case poverty. That’s what social medicine is. I’m a doctor, do I treat a fever when the underlying cause is malaria or do I treat malaria? It’s my experience that a lot of these diseases are rooted in these social contexts, that they are naturally part of diagnostic and treatment practices.